Of course this scam is not restricted to dog breeders, but this case is. Susan Ware has been a devoted breeder of Flat-Coated Retrievers for many years, always striving to improve the breed. (she actually retired from breeding a few years ago)

If you are not familiar with this fraud, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) describe it like this: The victim gets a call from someone posing as his or her grandchild. This person explains, in a frantic-sounding voice, that he or she is in trouble: There’s been an accident, or an arrest, or a robbery.

In Susan's case, the fraudsters claimed to be her grandson who was a passenger in a car that was stopped by police. A large number of drugs were found and he had been charged with trafficking (none of this was true of course). Susan says they knew a lot about her grandson and were very convincing. She withdrew all her money from the bank and turned it over to a "courier" that came to her house to collect it.

Susan's Daughter Caroline added: "The victim of fraud for this GoFundMe is my mother, a widow of 30 years, 83 years of age left with nothing after this scam. Aside from being frauded, the emotional distress has been far more than she can take. Financially it has been very delicate as my mother was nearing the end of a reverse mortgage, this fraud has truly depleted her funds to nil. Any generosity would be greatly appreciated in this difficult time." You can help by going to the GoFundMe page HERE and by sharing this to you friends.

My interest since early childhood has been in breeding and training dogs. My young family, in the late 1980’s was more interested in camping and adventure sports so we spent most of our time on canoe trips and expeditions and I was limited to one family dog. Then I came up with an idea. If we just got a couple of Huskies, we could go winter camping too. The dogs could pull the gear and we would be able to snowshoe or ski along with them.

Well a couple of Huskies just wasn’t cutting it, and the dogsledding caught on with the family so we started accumulating sled dogs and joining sledding groups. We had to have more dogs to keep up with our new sledding buddies and the first part of my dream came true when I started breeding Siberians. A breeding kennel has to have a name and since Siberians and sledding exemplify the north and my husband was involved in land surveying at the time we settled on DueNorth as our kennel name and registered with the CKC in 1991 . Needless to say the canoe tripping was now a thing of the past with up to thirty sled dogs to care for year round. Eventually as they and we aged the sledding took a back seat and, since we had a kennel anyway and my husband, by this time, was excellent at picking up dog poop we started to take on boarders but kept the DueNorth kennel name. So the DueNorth name still brings back fond memories of long canoe trips in northern Ontario and multi day dog sledding expeditions with like minded friends and our beautiful Flat Coats have never question why they're registered names begin with DueNorth.

Clicker training, Compulsive Training, Pure positive? Negative reinforcement? Positive punishment?? I just want my dog to stop pulling on the leash! But these are a few of the methods the professional trainer will consider when assessing you and your dog. So which method works best? Well the definitive answer is - it depends. It depends on the personality and learning style of both the dog and the handler. The handler must understand the philosophy underlying the training method employed or the whole endeavour will be doomed to failure. For example, clicker training, a method in vogue at present, can be an effective tool, but the method is complicated and if not well understood can be confusing for the dog and frustrating for the handler. The idea behind the clicker is to signal that a reward is coming for a wanted behaviour. The clicker can mark the exact moment of the correct behaviour with the reward to follow, but among the common mistakes are badly timed clicks or failure to provide the reward. Pure positive or motivational training employs the use of rewards to reinforce good behaviour, and ignores all bad behaviour. Pure positive training is feasible, but requires time and patience to control the rewards the dog receives for behaviour. Some activities such as jumping up or chasing squirrels are intrinsically rewarding, the activity is its own reward. Some variations encourage controlling the environment by restricting the dog so that all reinforcement comes from the handler. The use of head halters such as the Halti to control pulling on the leash for example prevents the dog from pulling, but does not train him not to. The compulsive methods have been proven effective but many worry about harming their dog. The tools used, such as pinch or prong collars can be misused if the method is not properly understood. Although technically a “punishment” in the operational sense, these methods do not employ punishment in the common use of the word and are in no way abusive. Correctly used, these tools are used strictly as a method of communication between the handler and the dog. Even more misunderstood is the proper use of electronic collars (shock collars). These tools have received a horrendous reputation from misuse by untrained individuals. The proper use involves a slight stimulation that signals the dog that we need his attention. Nothing more, there is no shocking involved. Like clicker training, timing is critical and proper training is imperative.

So there she is lying at your feet gazing expectantly at your face. Yes I love you too you are thinking, but is she really feeling affection for you or is she just hungry.

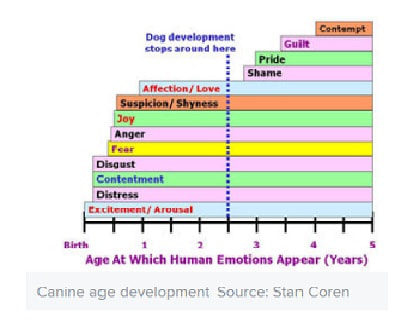

Any dog owner can tell you that they respond to human affection. Several scientists such as Dr. Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University and the author of “What It’s Like to Be a Dog” have managed to train dogs to remain perfectly still while in a functional MRI. What Dr. Berns and others have found is that the canine pleasure centres respond at least as much, and in 20% of cases more to praise and affection as they do to food. So OK, dogs respond to affection, but do they actually have feelings of affection themselves. Researchers long ago identified the hormone oxytocin as the mediating chemical in human bonding. When humans hug or gaze into each others eyes, they each experience increased levels of the hormone. A 2015 study in Japan found dogs and humans were engaging in cross-species gaze-mediated bonding using this same oxytocin system. That is to say both the dogs and humans experienced elevated levels of oxytocin when gazing at each other. As we learned in Science Sunday a few weeks ago about " puppy dog eyes", wolves will not engage humans with eye contact and so do not bond with humans the way dogs do. In the field of genetic research studies looked at the phenomenon of hypersocialbility in humans, a malady know as Williams syndrome. UCLA geneticist Bridgett vonHoldt discovered in 2009: Dogs have a mutation in the same gene responsible for Williams syndrome in humans. Dogs, like humans with Williams syndrome show a desire to form close connections with those around them and the Williams syndrome gene mutation may be partially responsible. Numerous studies have equated canine development to that of an approximately 2 year old child. So do infants experience affection? The capacity for emotions in humans develops throughout early development. In the chart below we see that since canines and humans develop at about the same rate up to about 2.5 years, love and affection is the last emotion to develop in dogs.

So do they really love us? What ever love is, our dogs at least appear to exhibit it so lets just take it at face value.

Math problem for Fido: if you have three bones and Mrs. Jones takes one away, how many fingers will she have left?

Well actually dogs and many other animals are capable of solving simple math and not just through trick cues from their owners. Some of the first research into canine numeracy turned out to be flawed. The dogs were presented with two choices of a large or smaller ball of hamburg and it was found that they had no preference as to size. This research was flawed in that it was discovered that the placement of the food was uncontrolled and the dogs were actually choosing the closest, perhaps demonstrating some distance measuring skills. With that discrepancy accounted for it was found that the dogs can easily compare size and choose the larger helping demonstrating quantitative comparison skills. Another related task is to estimate the number of things in a group, or at least compare the number of things in two groups. This is known as the approximate number system and humans do quite well at it. For instance most of us can estimate which crowd has the most people (with the exception of Donald Trump estimating inauguration crowd sizes). Dogs can also estimate which pile of kibble has the most pieces in it. This has been formalized in the laboratory by training dogs to select a computer screen which has the most dots to receive a reward, proving that dogs do understand the approximate number system in making quantity comparisons. Studies with human infants have found that there is an innate ability to do simple mathematics. The babies were shown a toy or something of interest, and then a screen was placed in front of it. The researcher would then place another item behind the screen and the screen would be lifted. In some cases the researcher would secretly remove one of the items before the reveal. In cases where the number of items revealed was unexpected, the subject baby would spend much more time staring at it. This suggests that infants have made the mental calculation and are now surprised to find that the number of items they are seeing is different than what they expected. The same study has been done with dogs using treats to hide behind the screen and the results were the same as with the infant studies. The dogs demonstrated the surprise reaction even when finding three treats when they were expecting two. The understanding of numeracy was further formalized by dogs trained to be still in functional MRI (fMRI) machine. The subjects were shown a screen with dots that varied quickly while in the fMRI and they found that the variance in the number of dots on the screen stimulated similar areas of the brain as in humans. “These findings support our understanding of the Approximate Number System; previously, these effects had only been demonstrated behaviorally in dogs, so this is an important contribution to our understanding of canine cognition,” says Krista Macpherson, a canine cognition researcher at Western University in London, Canada. Many of us have seen this numerical ability in our own dogs, for example in retriever trials when a multiple retrieve is called for the dog must not only remember the approximate location but the number of retrieves. Flock guardians must also be able to at least estimate the size of the flock. So all that being said, I see no reason why Twist should not have my tax return finished by the due date.

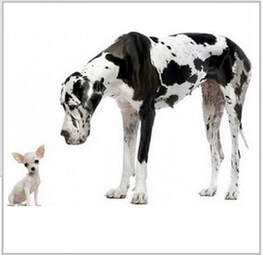

Four legs, a tail, must be a dog. No wait maybe it's a cat or ferret. Dogs do not seem to have any problem recognizing members of their own species, notwithstanding the myriad of shapes and sizes that they come in. We know dogs are renowned for their olfactory competence, so is that how they do it? Anecdotal experience suggest that they have already made the species identification before the serious butt sniffing begins. So what cues are they using to identify a stranger as a dog or not a dog. For that matter how do we do it? Small children can discern between a dog and a cat even among broad morphological samples. What differentiates "catness" from "dogness". So are dogs able recognize their con-specifics solely by sight?

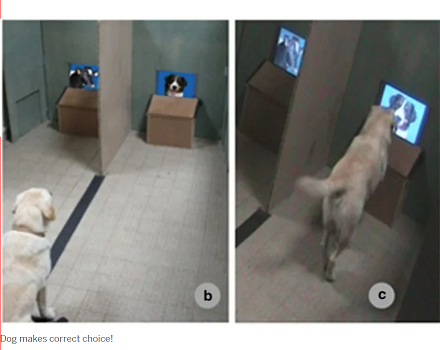

A team of researchers based in France took on this question, publishing their findings in Animal Cognition in 2013. Nine dogs were used in the study, a Lab, a Border Collie and seven mixed breeds, all living in homes and normally trained as pet dogs. The dogs first went through a training phase where they were shown two pictures, one of a dog (always the same dog) the other screen was either all black, all blue, or had a picture of a cow’s face. The dogs were rewarded for selecting the picture of the dog by approaching the screen. All nine subjects learned to do this in three sessions.

Then came the test. Dogs were presented with a wide variety of never-before-seen dog faces paired against never-before-seen non-dog faces. As before, dogs had to approach the dog image and avoid the non-dog image to get a treat. The none dog faces included a wide variety of domestic and wild animals and even humans. All nine dogs in the study were able to group all the dog images, regardless of breed, into into a single category despite the diversity of breeds. We still do not know how they do this, that is to say what is the "dogness" of a dog that makes it recognizable by dogs or humans.

Recent developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have brought computers to a similar place in recognition. As I understand it (which is not very well), convolutional neural networks are shown huge samples of dog pictures tagged as dogs. The AI system learns to identify dogs from this process, the accuracy dependent on the size of the sample. Interestingly again, we do not understand what the system is identifying to discern "dogness" . Even more impressive these systems can now identify dog breeds. So whether its dogs, computers or kids there's something about dogs that render them recognizable.

Boarding clients dropping their dog off often tell us that "he doesn't like men", explaining they believe he was abused by a man in a previous home. But I always wonder if the dog is just afraid of strangers in general without regard to gender.

Can dogs even discriminate between human genders? A 2014 study devised an experiment to determine just that. Fifty-one dogs were played a prerecorded male or female voice in the presence of a man and a woman. The responses were scored as correct or incorrect from both the direction of the first look and the total gaze duration towards each person after the voice presentation. The interesting element from this study was that dogs raised in a single person home identified male or female incorrectly 71% of the time, while those in homes with at least one male and one female were correct 80% of the time. So that it seems that dogs raised only by females may not understand what a male human is. Anecdotally, in our experience people reporting this problem generally have rescue dogs often with unknown background. A 2009 study in the state of Michigan found that 92% of dog rescue organizations are staffed by female volunteers. This preponderance of women may exacerbate the problem of the dog not being able to identify a male. But why should men be so scary. It may come down to the Ying and Yang of gender difference. Men, generally, are bigger, louder, more assertive and forward than women. In extreme cases even people can identify when an assertive male walks into a room, its' reasonable to assume that dogs will clue into this in even less extreme cases. So the solution, as with many canine behaviour problems is socialization. Pups need to be gently introduced to every type of situation possible, especially during their "fear periods". Dogs go through two periods when bad experiences can be imprinted for life. The first is actually two periods, the first at five weeks, when pups demonstrate a strong fear response toward loud noises and novel stimuli, then again at seven to twelve weeks, the puppy is very sensitive to traumatic experiences, and a single scary event may be enough to traumatize the puppy and have life-long effects on his future behaviours. In our own breeding program we begin to introduce novel odours just a few days after birth, and in the puppy pen present every possible type of surface and toy.  DueNorth's Puppy Playpen DueNorth's Puppy Playpen

The second fear period occurs between six to fourteen months. In the wild, dogs at this age are allowed to go on hunts with the rest of the pack, and it may be a survival strategy for them to learn to respond fearfully to the unfamiliar.

There are undoubtedly cases where a fear of men was caused by abuse, but it is more likely that fear of men, or anything else was a result of incomplete socialization at critical periods in the young dog's life.

Most human parents are all to familiar with adolescent angst. Surly, uncommunicative, moody, argumentative and flippant, all the touchstone behaviours we fondly remember (or look forward to) from adolescence. But do dogs experience similar behavioural stages? A new study published by the Royal Society looked into just this.

The researchers started with three proven aspects of human adolescence:

To study the behavioural changes during the adolescent period, the team followed a group of guide dog puppies (German Shepherds, Labrador Retrievers, and Golden Retrievers plus mixes of these breeds) over the first year of their life. They wanted to see whether the dog-owner relationship would parallel the parent-child relationship in humans. The study was carried out partially by questionnaire by both the carer and the trainer on 285 subjects and by behavioural tests on 69 of the same group of guide dog trainees. Data was collected when the dogs were 5 months of age (which should be preadolescent), 8 months of age (which should be right in the middle of the "teenage" puberty phase) and 12 months of age (which should be pretty much at the end of the adolescent phase for most of the dogs). ( see last week's Science Sunday on ageing in dogs) The first question concerning onset of puberty and secure attachments to their carer was answered using 70 bitches from the study since puberty onset is obvious in females at first estrus. The attachment to carer was scored on compressive questions about attachment behaviours and separation anxiety and even adjusted for confounding behaviours such as general anxiety. Attachment and attention seeking was positively correlated with the age at which bitches had their first estrus compared with their breed mean. Bitches that displayed more attachment and attention seeking behaviour at 5 months of age entered puberty earlier, exactly as in humans. The second question concerning increased conflict behaviour toward the carer was evaluated with 96 of the subject dogs (41 M: 52 F) in a simple behavioural test. All dogs had mastered the sit command by 5 months of age, and were tested at 5 months (pre-puberty), 8 months (adolescence), and 12 months (post adolescence). The results were clear, the adolescents resisted commands from the carer, but not from a stranger (the trainer in this case). Again this was analogous to behaviour in adolescent humans. The third question "heightened conflict behaviour when carer attachments are less secure", was addressed through the questionnaires. Mirroring the transitory adolescent-phase of conflict was a phase of higher scores for Separation-Related Behaviour towards the carer. Scores for Separation-Related Behaviour were 36% higher at adolescence (8 months) than pre-adolescence (5 months) and post-adolescence (12 months). The higher Separation-Related scores at 8 months co-related with lower Trainability Scores with respect to their carers. Scores of Attachment and Attention Seeking did not change with age, but they were correlated with Trainability Scores at 8 months of age only. Another consideration when attempting to train through adolescence is the canine fear periods. The second fear period occurs between six to fourteen months, co-relating with adolescence. Care must be taken not to cause deep seated fears which are very difficult to overcome during this period. So it seems that adolescence in dogs is not unlike human teenagers but thankfully doesn't last as long.

When I started to research this topic for Science Sunday, I expected to find some evolutionary advantage to blue eyes in northern climates since blue eyes are mostly associated with Siberian Huskies. In humans, blue eyes co-evolved with light skin and blonde hair in northern regions then spread through Europe. In humans lighter skin allows for better synthesis of vitamin D from the sun. This was an advantage in northern regions where sunlight levels are lower. The process works like this: the oil in our skin reacts with sunlight to produce vitamin D which is then absorbed through the skin into the blood stream. In equatorial climates, the sun is intense enough for this process to work even in darker skinned individuals. Dogs produce the same oil on their skin but any vitamin D that is produced is absorbed into their fur. This works okay for cats who spend a lot of time licking their fur, but dogs must get most of their vitamin D from their diet. This was traditionally from meat but more now from manufactured dog food supplemented with vitamin D. So blue eyes did not confer the same evolutionary advantage to dogs as it did to humans.

They did not inherit blue eyes from their predecessor, the wolf, since no wolf species have blue eyes. A genetic study released in October 2018 looked for the genetic markers associated with eye colour. The study, by Embark Veterinary, looked at the genome of 6000 dogs and compared some 200,000 genetic markers. The team found a mutation on chromosome 19 that was strongly correlated with subjects reported to have blue eyes. The gene, called ALX4, has not been associated with eye colour in humans or mice, meaning that the mutation is completely new to researchers. So we now know where blue eyes come from, but we don't know why. Siberians are not the only breed to sport blue eyes. Other breeds include:

The answer to the prevalence of blue eyes may be more mundane than evolutionary advantage. John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin-Madison speaking about the prevalence of blue eyes in humans said “This gene does something good for people. It makes them have more kids.” So just as blonde haired blue eyed humans breed more often the evidence suggests that blue eyes in dogs was also selected for simply because of their piercing allure.

We recently had a boarder in the kennel with a two word name (Harry Potter) which made me wonder what kind of names are more effective for communication. Veterinary behaviourists have shown that a dog's name is more of a cue than a personal identifier. They respond to their name because something happens after they hear it. The theory is that unlike human's response to "I am my name", dogs respond simply because something good is going to happen when they hear their name.

That being said there have been studies into the types of sounds that elicit better responses. One study showed that four short notes were more effective at eliciting a come response and increasing motor activity levels than one longer continuous note. So that choosing a name that can be adapted to different tones can work well. Two syllable names work well for this. For instance, "Glorrr-yyy" may be more effective than single syllable "Spot" for recall. On the other hand, other studies show that dogs respond quicker to short choppy sounds with a hard consonant. There are lots of practical considerations, such as avoiding similar sounding names in multiple dog households. Avoid names that sound like commands you may want to use later. Our 13 year old grand-daughter learned this when she was trying to teach "over" to her Golden Retriever Clover. Naming your dog with a person's name may get you some strange looks at the dog park when you call "Steve Come".

We've all heard stories of dogs finding their way home, sometimes from hundreds of kilometres (click here to read some). But how do they do it? Many animals and even insects have been shown to be able to navigate with the help of the earth's magnetic field, an ability known as magnetoreception.

What seems like a rather odd study in 2013, published in Frontiers in Zoology, researchers tried to prove that dogs have this ability by recording their alignment when they were pooping or peeing or just marking territory. They measured the direction of the body axis in 70 dogs of 37 breeds during defecation (1,893 observations) and urination (5,582 observations) over a two-year period. They were able to conclude from this data that dogs preferred to excrete with the body being aligned along the North–South axis under calm magnetic field conditions. (the correlation was extinguished when the magnetic field was unstable). Beyond mapping where your dog poops, this study did establish that dogs are capable of magnetoreception. The actual mechanism of magnetoreception in dogs was discovered in a 2016 study. Cryptochromes are a protein involved in the circadian rhythms of plants and animals, and possibly also in the sensing of magnetic fields in a number of species. Cryptochrome 1a is located in photoreceptors in birds' eyes and is activated by the magnetic field. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt have detected cryptochrome 1a in photoreceptors in several mammalian species including dogs. In a further test in 2018 to prove that dogs have this ability, dogs were trained to locate a simple bar magnet. After removing confounding factors of site and smell, 13 of 16 dogs were able to locate a magnet with no other clues than the magnetic field. Finally a new study released earlier this month used hunting dogs to find out if they are using their magnetorecption capability to find their way back to their owners after a hunting run. Between September 2014 and December 2017, the study team equipped 27 hunting dogs of 10 different breeds, with GPS trackers. These dogs were allowed to roam in forested areas away from buildings, roads and powerlines. Dogs ran individually and returned on their own. Trips took between 30 and 90 minutes. Owners hid close to the location where the dog was released. The GPS data, from a total of 622 excursions in 62 different locations in the Czech Republic, were then compiled and analyzed. Most of the dogs simply followed their own scent back, a method know as tracking. However in 233 cases, the dogs took a novel route back, a method known as scouting. Interestingly, the scouting dogs began their trip back with a run in the north/south direction, regardless of the direction of the trip. This "compass run" was surmised to be instrumental in orienting the dogs to the magnetic field and the direction home. The scouting dogs returned faster to their owners than the dogs using the tracking method, in which they just came back the same way they went out. So looks like not only will Lassie find her way home by herself, she will also poop in the north/south direction while doing it.

"C'mon get off the couch it's time for my supper." We have all seen or heard of stories about dogs knowing when the school bus is due, or when it's time for their daily walk, but obviously they do not understand clock time in the same way that we do. So how do they understand the passage of time? There has been surprisingly little research into this fascinating topic.

Without clocks even we do not have a very good sense of time. If we are engaged in some activity we are interested in, time seems to fly by, while on the other hand if we are stuck with some mundane task we abhor, it seems to take forever. But that forever is related to a clock. If we didn't have a clock we would not have any idea how long each of these events actually took. So how can dogs know when they spend most of their time sleeping? I think we need to distinguish between two aspects of time, time of day and duration of events. Knowing when the school bus is due requires dogs to know the time of day. There are several theories about how they do this. Dogs, like most mammals, have a circadian rhythm, an internal sense that tells them when to sleep or when to be active. Perhaps it’s their bodies, not their minds, that can detect roughly what time it is. So if in the mid-afternoon your dog is used to getting her food, her body gets hungry around this time each day. Another theory expands on dog's amazing ability to pick up on external cues and associate them with another event. For example maybe you start getting dinner ready just before the school bus arrives or another bus passes every day just before the kids get home. There have been studies on how dogs perceive duration of events, specifically how they greet you when you have been gone for a period of time. We have all seen that they don't get too excited when we come back from getting the mail but on the other hand if we have been gone for more than two hours we get quite a happy greeting. One researcher attributes this to their well know sense of smell. The longer you have been gone, the more your scent in the house diminishes. They tested this by leaving the owners' scent around the house and evaluate the return greeting after various lengths of time. The dogs did not respond the same as long as the scent was present. At any rate there does not seem any need to purchase a Rolex for Fido just yet.

Hard to believe there has been so little research on this crucial topic. Most of what has been written are just theories. Dog behaviourists believe that a dog’s need to perform the bedtime ritual of turning around in circles before lying down is inherited. Their wolf ancestors living in packs do this on a regular basis. The theories speculate a multi purpose of sniffing the air for predators, chasing snakes, bugs and rodents away and trampling down the grass to make a comfortable bed.

There might be a social element to circling, too. Wolves and wild dogs often travel in packs and have strict social hierarchies. When they bed for the night, they sleep in a tight circle to protect each other and stay warm. Circling might be a way of marking one's sleeping space and establishing a spot in the circle, the canine equivalent of calling first bedsies. My favourite go to guy when researching these articles, Dr. Stanley Coren, in Psychology Today, found a similar dearth of scientific evidence for this behaviour, and so did his own study. He was going on the theory that the circling was primarily for comfort and so devised an experiment with both a flat mat and a crumpled up shag rug. Each was placed in a 3' x 6' pen and pet dogs were brought in one at a time. The owner and experimenter sat down some distance away and waited until the dog decided to lay down and recorded their behaviour. This was done for 31 dogs in each situation. The results were quite clear. On the smooth surface only 6 dogs (19%) circled at least once before laying down. On the uneven surface 17 (55%) circled at least once before laying down. So it seems that comfort is at least one reason for the circling behaviour. If the behaviour becomes excessive, it could be a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a small number of dogs. Maybe us humans, instead of spending large amounts of money on fancy beds could just start trampling down the one we have. Try convincing your partner of this.  Using food to lure your dog into a sit position is one of the first training "tricks" we learn, but how does rewarding a dog actually elicit the desired response? Humans often use a sort of experimental approach. The sequence might go like this - enter a dark room, flick light switch, room lights. The action of flicking the switch had the desired effect and we usually use the same approach when presented with the same situation, had it not worked we would try another solution. Psychologists, of course have a term for this; it's called "win-stay-lose-shift strategy". If it worked keep doing it , if it didn't, try something else. Is this the strategy that dogs are using when responding to reward based training? To find out, Molly Byrne, and a team of researchers at the Department of Psychology, Boston College looked at this very question. A group of adult dogs (323) were taught that if they touched an inverted cup they would receive the treat hidden underneath. Next they were presented with two cups located equal distance from the dog and the dog was restricted to selecting only one of the cups per trial. The paper cites previous work by the same team to eliminate olfactory cues. On subsequent runs it was recorded whether they chose the same cup or the other cup and whether the previous run was successful. To eliminate the possibility of previous conditioning, the experiment was repeated with 334 puppies. Quoting from the study:

Our takeaway from this should be the importance of treating every time when trying to establish a behaviour to avoid the dreaded "lose-shift" side of the equation. "But Pat, wait" I hear you saying "you always say you are a Balanced Trainer, have you suddenly joined the pure positive crowd." Not at all. Rewards are useful for establishing a behaviour, but once the desired command is learned and established its time to start phasing out the treats in lieu of praise, occasional treats and discipline. Its like gambling, the gambler is not rewarded every time, but maybe next time. Knowing when and how is where the professional part of professional dog training comes in. What do you think?

Recognizing one's self in the mirror requires sophisticated cognitive function and a sense of self awareness. Children do not acquire the ability to recognize themselves in the mirror until 18 - 24 months of age. This was demonstrated in experiments involving putting red dots on their faces. Younger babies showed little interest in the facial decorating, however the older kids began touching their own faces indicating that they understood it was their own reflection they were looking at. Similar experiments have been carried out with other primates and even dolphins and magpies showing some degree of self awareness. That is they understood that this is "MY" face, it is part of "ME". When dogs first encounter a mirror they respond as if it is another dog. You may have seen this yourself when a young dog attempts to play with the reflection as in this video, or take himself as a threat and start growling. Eventually most dogs become habituated to the reflection and just ignore it. So does this mean dogs haven no sense of self awareness and therefore lack consciousness? These studies all centred on animals whose primary sensory input is vision. Dogs, as we all know, are olfactory centred creatures. University of Colorado biologist Marc Bekoff tried an experiment involving one of dogs' favourite pastimes, sniffing pee. Over the period of five winters, he relocated yellow snow to different locations, including those of his own dog whom he had earlier walked. On the next walk each time as expected his dog would stop and sniff the yellow snow and in most cases pee over top of it. But when he encountered his own relocated yellow snow, would briefly sniff then ignore. Bekoff concluded that we can say that dogs do have some of the same aspects of self-awareness that humans have. Mirror reflections, having no smell, just aren't interesting enough to demonstrate it. Other experiments have been done to see if dogs understand how mirrors work. Tiffani Howell and Pauleen Bennett of the Anthrozoology Research Group set up an experiment in which one dog owner would direct the dogs attention to the mirror, while another owner holding a toy or treat could only be seen in the mirror. Out of 40 participants only 7 turned to look at the second person. As I recall high school science class, the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. This probably means as little to Twist as it now does to me, but he never forgets how to sniff out a treat. References: What do Dogs See in Mirrors, Julie Hecht, Scientific American, 21 August 2017 Does My Dog Recognize Himself in a Mirror?, Psychology Today, Stanley Coren, July 7, 2011 What Do Animals See in the Mirror? Liz Langley, National Geographic, February 14, 2015 |

Other Topics |

|

Serving Peterborough and area for over 20 years at:

2106 McCracken's Landing Rd Douro-Dummer ON K0L2H0 Phone:705-652-0682 email: [email protected] |

Vertical Divider

|